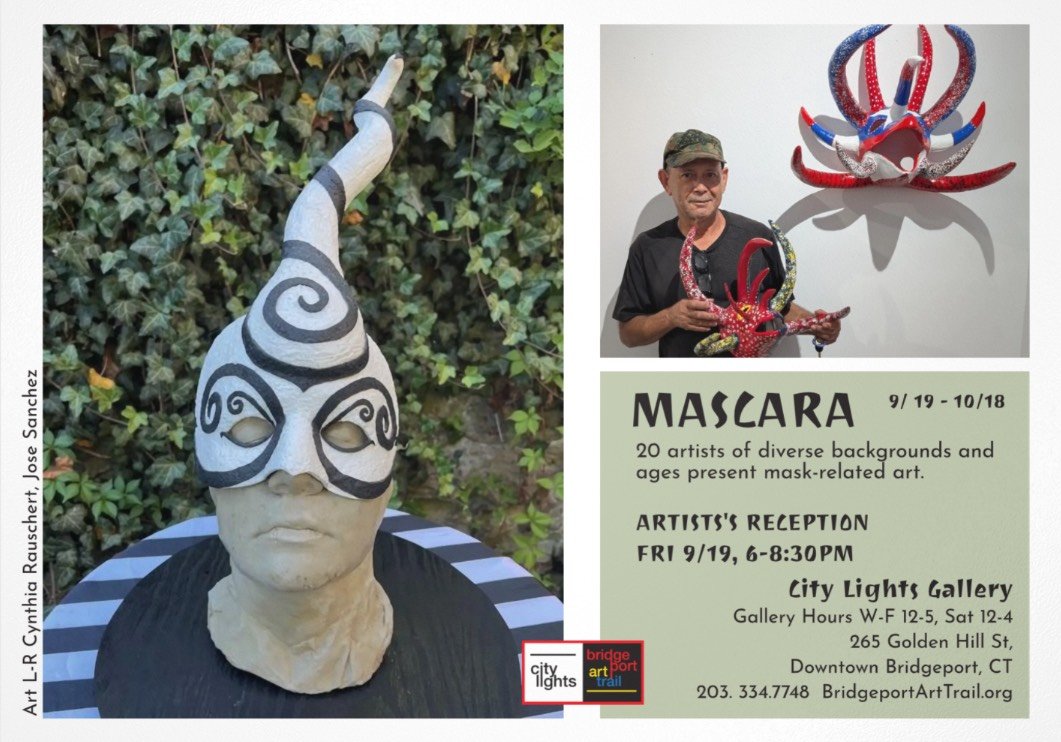

“Mascara”

Artists’ Reception September 19th, 6:00 - 8:30 PM

Meet the artists, munch and mingle on Friday September 19, 6-8:30 pm. The exhibit runs to October 18. Regular gallery and frame shop hours are W-F 12-5, Sat 12-4. 203.334.7748 clgallerybpt@gmail.com

Throughout history, masks have been an integral part of man's culture and ritual. Mascara is the Spanish word for mask. From traditional Puerto Rican Vejigante masks to contemporary expressions, City Lights Gallery presents the mask related artwork created by 20 artists from diverse backgrounds and ethnicities during Hispanic Heritage Month. Festivities on Friday 9/19 begin with a Downtown Parking Day and a Salsa Party produced by Colorful Bridgeport. Come downtown early for Parking Day and see artist Carlos Biernnay build a mask.

Exhibiting artists are Patricia Aguilar, Erika Ayala, Carlos Biernnay, Anthony Bryant Jr, Jose Rafael Cabrera, Al Castellon, Ronald Ferrucci, Rebecca Greenberg, Kit Grindeland, Suzanne Kachmar, Iyaba Ibo Mandingo, Jay Maggi, Elliana Mesa, Larry Morse, Yolanda Vasquez-Petrocelli, Samuel Pintos, Cynthia Rauschert, Daniel Rivera, Jelena Sanchez, Jose Sanchez, Ellen Tresselt, Paola Figuerao Perez, Daniel Lanzilotta.

The Legacy of Loiza

In the town of Loiza in the northeastern coast of Puerto Rico there is an inconspicuous yellow house that holds Artesanias Castor Ayala, a space full of art and creativity. An art and souvenir shop made by Don Castor Ayala in the 1950s. This special place holds one of Puerto Rico’s greatest artistic treasures–vejigante masks.

Vejigante masks are a cultural treasure of Puerto Rico. They were brought over from Spain during colonization, dating all the way to the middle ages in Spain where they were used as covers for those who publicly over-celebrated and over-indulged right before they gave those things up for Lent. When they reached Puerto Rico, they mixed with the culture of the Native Tainos and the African Slaves to become something uniquely Puerto Rican.

Vejigante masks are used throughout the island, but are especially rooted in the traditions of 2 towns, Ponce and Loiza. En Ponce, the vejigante masks are used during Carnival, right before Lent and made of paper-mache molded on a fixed form,which is more like the original Spanish masks. In Loiza, the masks are primarily used for the Fiesta of Santiago Apostol (St. James) in July. These masks are made of coconut husks and the carvings of the masks show more of a connection to the carved wooden masks of West Africa.

This makes sense since Loiza is the epicenter of everything Afro-Puerto Rican. Loiza, hidden away by raging rivers and rough terrains was a safe haven for many runaway slaves and until the 1970s when a bridge was constructed connecting it to the rest of the island, it remained mostly insular, its African roots incorporating and mixing completely in the fabric of the town.

And here is where we come back to Don Castor Ayala. Don Castor opened his artesania and right next door a school for Puerto Rican folkloric dance, specifically Bomba. Bomba, like the vejigante mask, is completely Puerto Rican, and like the Loiza vejigante masks, is deeply infused with African roots, from its use of drums, to its call and response style. Bomba has been danced since the 1500s. It was used by slaves and escaped slaves as a form of communion, a way to get information across, both current like when there would be a rebellion, to things from the past, to make sure the roots were not forgotten. Now it is also used to maintain community, to keep history and roots connected and alive. And like in the past, Bomba has recently been used at Black Lives Matter Protest as a form of resistance and protest. Don Castor knew that these two art styles from his hometown of Loiza were important. He taught himself to make masks and started selling them, and with his brothers, he opened the dance school and made sure to teach other generations. Now, even though he is gone, his legacy lives on. He is still known as the father of vejigantes in Loiza and his school still teaches others of bomba. His children keep these places going and keep the dream of their father alive.

But not only them, his granddaughter, Erika Ayala, who lives and works in Bridgeport, keeps his dream alive too. Even though she did not get the chance to meet him, she feels her connection to him through his legacy and work. An artist herself, she tells me about the importance of the vejiganate masks for her. They connect her to her people, to her island, to those who came before. They connect her to her grandfather. These masks helped preserve African culture and heritage, they are the prominent symbol of Loiza. She sees these masks as heritage passed down to her that she can make her own through her art, but also as a mental mask she can wear to project and protect herself. And more than anything, she feels that these masks connect the diaspora to the land, the place that holds their past and calls out to them waiting for a response like in Bomba.

The people of Loiza have always known of their power, and keep making sure that their connection to their roots are alive and well. Don Castor knew this and knew the importance of art. He has left a legacy and a place in Loiza where his children keep his dreams and his roots alive, making sure the tradition of the Loizan Vejigante and the Loizan Bomba keep flowing on to new generations, and people like his granddaughter Erika Ayala. Her artwork is also exhibited in Mascara, the exhibition for Hispanic Heritage Month at City Lights Gallery. Her work connects us to Don Castor and all the people of Loiza, past, present, and future.

Wari Masks II, Samuel Pintos

Wari Masks II, Samuel Pintos

Sierro, Jose Cabrera

Sierro, Jose Cabrera

Just Smile, Jose Cabrera

Just Smile, Jose Cabrera

Poison Frog, Rebecca Greenberg

Poison Frog, Rebecca Greenberg

The Mask, Daniel Lanzilotta

The Mask, Daniel Lanzilotta

The Mask, Daniel Lanzilotta

The Mask, Daniel Lanzilotta

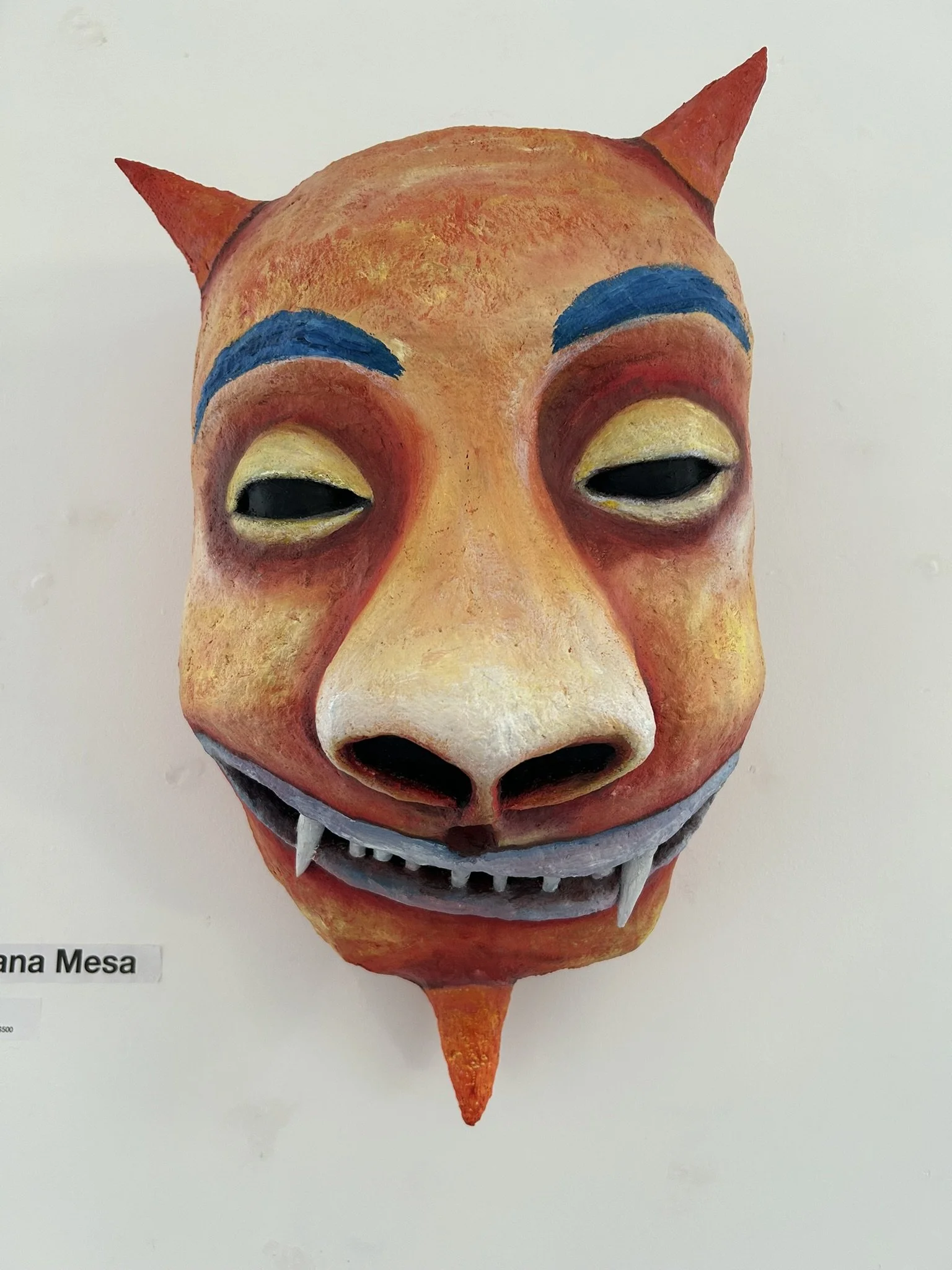

Untitled, Eliana Mesa

Untitled, Eliana Mesa

Untitled, Eliana Mesa

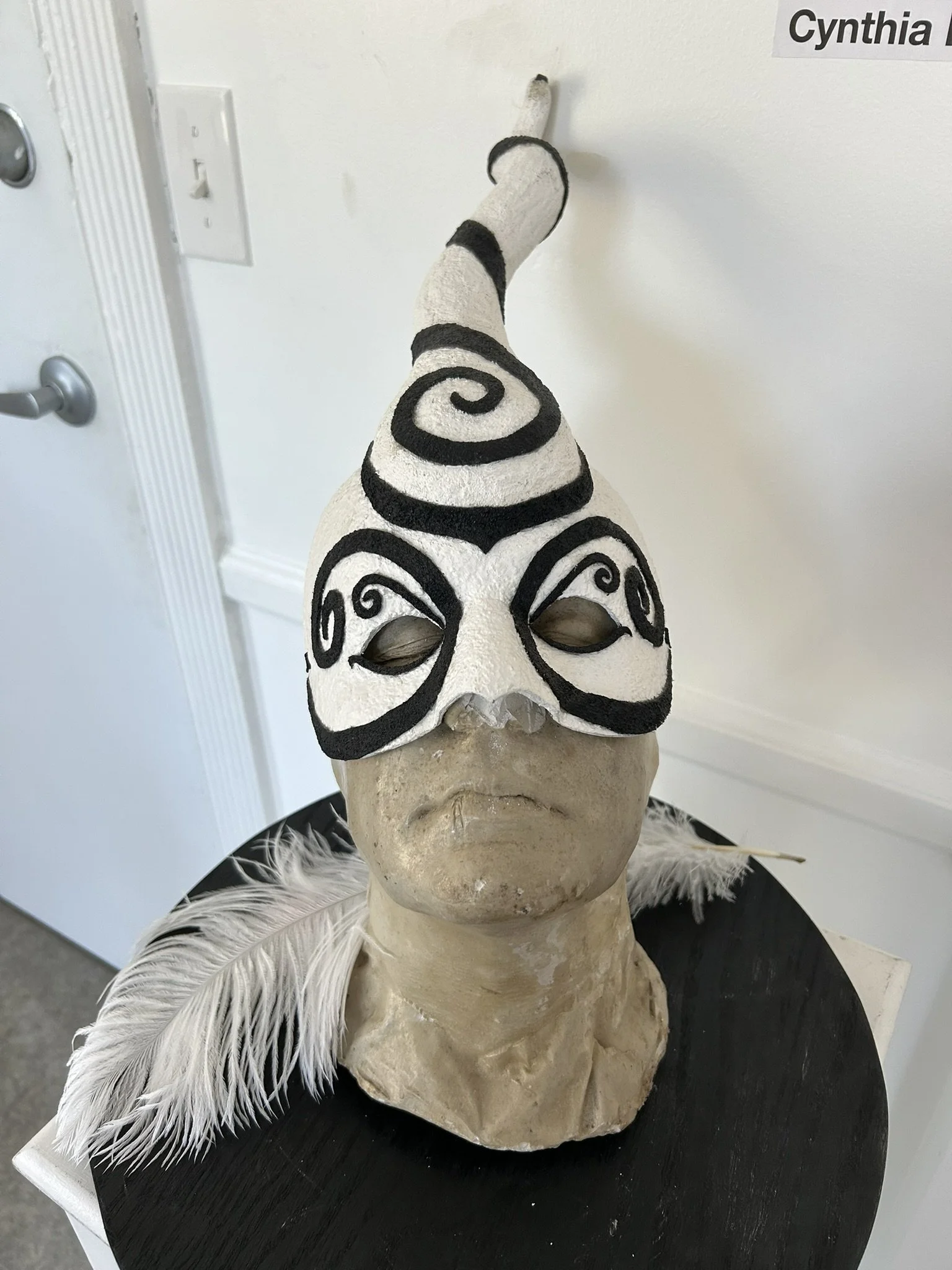

Geheimnis, Cynthia Rauschert

Geheimnis, Cynthia Rauschert

Geheimnis, Cynthia Rauschert

Gran Kollon, Paola Perez Figueroa

Norte Grande, Paola Perez Figueroa

Patagonia Selknam, Paola Perez Figueroa

Patagonia Selknam, Paola Perez Figueroa